21 May 2020 marked the 100th birthday of John Chadwick, FBA, the closest post-decipherment collaborator with Michael Ventris. The two worked intensely together for four years, according to the truly loving British Academy biographical memoir written by John T. Killen and the late Anna Morpurgo Davies. He was a richly honored scholar who shaped our field through his work, first with Ventris and then alone, on Documents in Mycenaean Greek (1956 and 1973) after first setting it on the right path, again with Ventris, in “Evidence for Greek Dialect in the Mycenaean Archives” in the Journal of Hellenic Studies for 1953. Chadwick’s The Decipherment of Linear B (1958, 1973) and The Mycenaean World (1976) opened the doors of our field to students and the reading public.

In a note of centennial celebration, we direct all those interested in Mycenaean studies to the above mentioned British Academy obituary Proceedings of the British Academy, 115 (2003) 133–165 .

We add here eight documents styled as birthday gifts from the PASP archives and library that reflect the human side of Chadwick’s influence on our field during its first quarter century post-decipherment. These are designed to be somewhat interactive in engaging your scholarly interests. Clicking any image will enlarge them and allow you to download them as files.

Birthday Gift Exhibit A

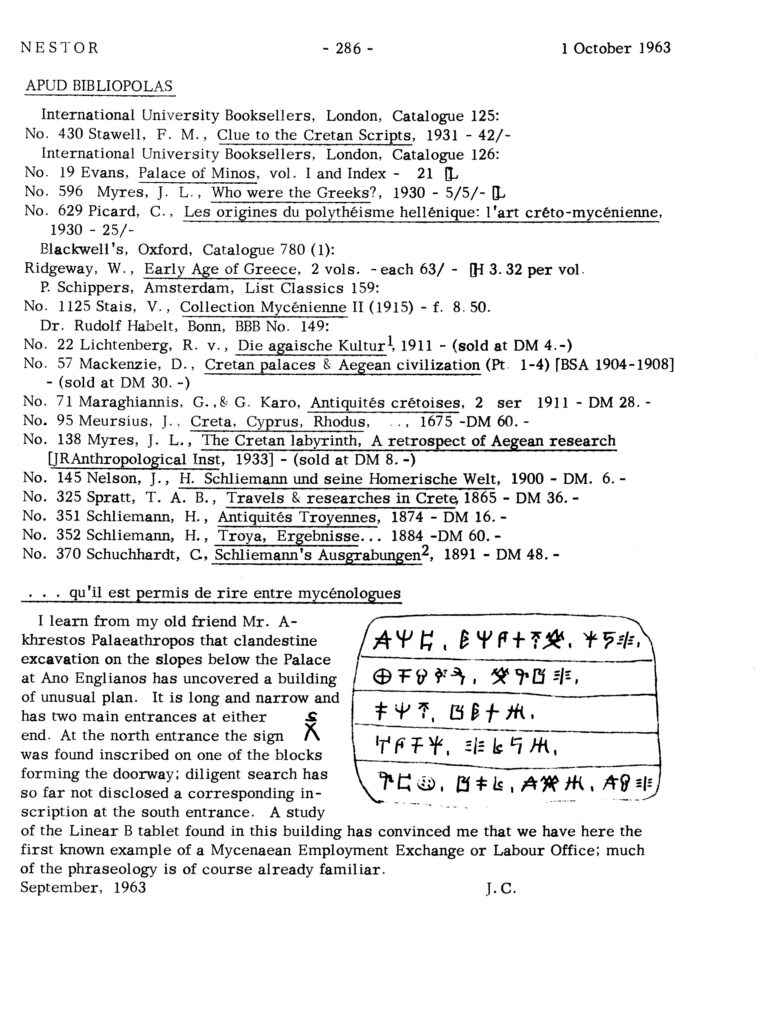

Birthday Gift Exhibit A is a tablet discovery reported to Nestor’s editor by one J.C. in the section of the old mimeographed and mailed Nestor 1 October 1963, p. 286: . . . qu’il est permis de rire entre mycénologues. This section of the monthly bibliographical journal of Aegean prehistory studies is lamentably now defunct.

Information about this tablet find is attributed in the Nestor notice to an old friend named Mr. Akhrestos Palaea<n>thropos (aka Useless Old-Timer). The tablet purportedly came from the inside of a long and narrow building uncovered along the slopes below the Palace of Ano Englianos. The stone façade of the northern entrance of said fictitious building was marked by an inscribed ideogram VIR—we may compare for this idea the masons’ marks on the Peristeria tholos. The ideogram engraved on the building and the contents of the tablet find suggested to J.C. that the building functioned as a “Mycenaean Employment Exchange or Labour Office.”

See if you can read the entries and identify their sources in the Linear B repertory of tablets.

Birthday Gift Exhibit B

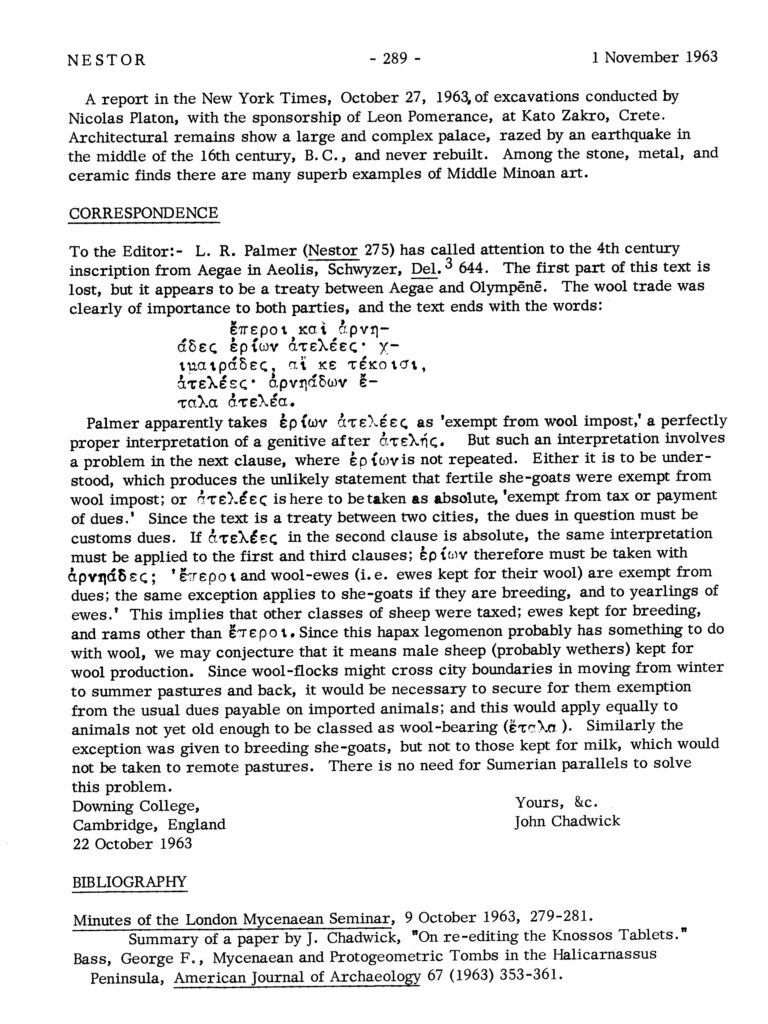

Birthday Gift Exhibit B is a more characteristically serious note (Nestor 1 November 1963, p. 289). In it Chadwick discusses a fragmentary 4th-century treaty inscription from Aegae in Aeolis dealing with wool-flocks and wool trade. It had been brought up and discussed by Leonard Palmer in an earlier send-out of Nestor (1 September, p. 275) in connection with the Linear B tablets monitoring various categories of flocks of livestock. Chadwick here proposes a different, more accurate reading:

ἔπεροι and wool-ewes (i.e., ewes kept for their wool) are exempt from dues; the same exception applies to she-goats if they are breeding, and to yearlings of ewes.

Chadwick then explains the terms of the treaty by bringing to bear practical knowledge of wool trade and flock management no doubt assisted by the work being done at that time by the young John T. Killen on the Knossian wool industry. Chadwick pays close attention to the wording and vocabulary of the text and the conditions of life in the ancient Greek landscape. In his opinion these proved to be sufficient for a correct interpretation. He closes: “There is no need for Sumerian parallels to solve this problem.” Indeed.

Birthday Gift Exhibit C

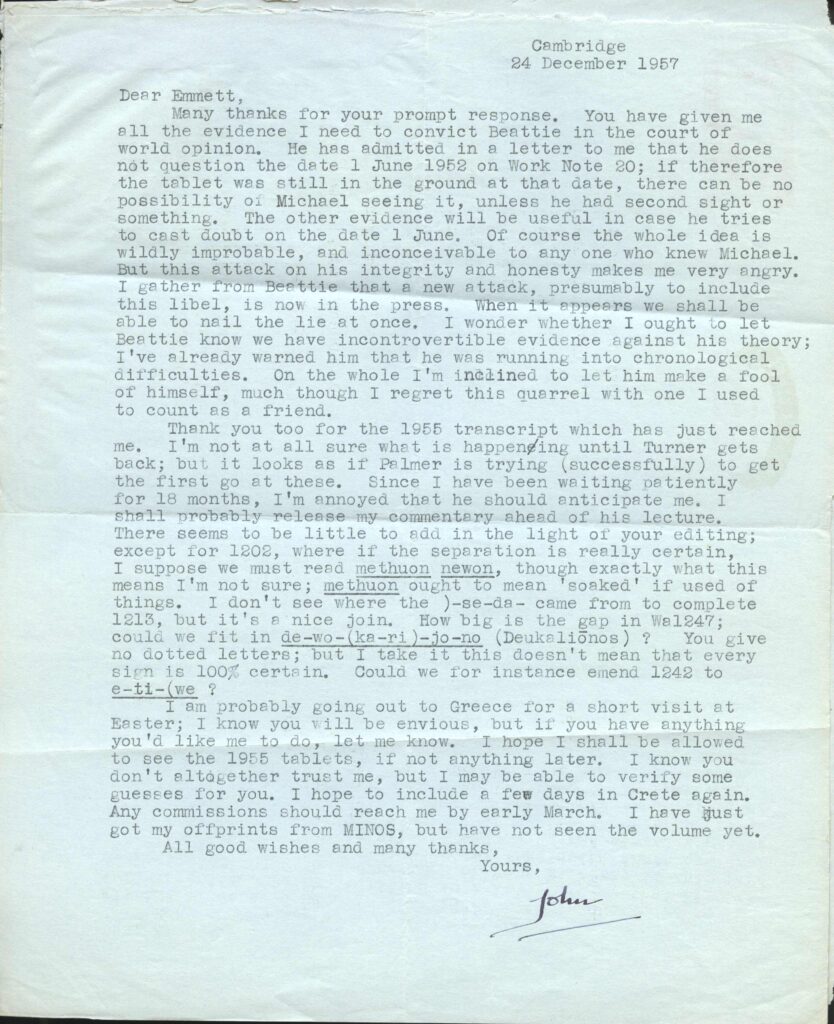

Birthday Gift Exhibit C written on Christmas Eve 1957 strikes a more somber note and reveals a justifiable undercurrent of emotion in defense of the integrity and honesty of Chadwick’s late revered and still lamented friend Michael Ventris.

Chadwick had just received, in the last letter sent from Bennett, proof of the date when the famous Pylos Ta ‘tripod’ tablet Ta 641 had been excavated. He was thus able to refute definitively the preposterous insinuation of Professor Arthur James Beattie (1914-1996) that Ventris had seen this tablet before he released Work Note 20 and had assigned values to the Linear B phonograms in order to ‘read’ the tablet correctly.

See Palaima, “Emmett L. Bennett, Jr., Michael G.F. Ventris, Alice E. Kober, Cryptanalysis, Decipherment and the Phaistos Disc,” in M.-L. Nosch and H. Landenius-Enegren eds., Aegean Scripts, (Incunabula Graeca 105, Rome: 2017) vol. 2, 771-788 for more on this kind of malicious postulating by Douglas Young and Beattie in articles somehow deemed worthwhile publishing throughout this period. A cursory examination of the logic of the arguments in these articles is enough to see that their claims have no merit. And yet….

It is no wonder that Chadwick writes:

Of course the whole idea is wildly improbable, and inconceivable to any one [sic] who knew Michael. But this attack on his integrity and honesty makes me very angry. I gather from Beattie that a new attack, presumably to include this libel, is now in the press.

Beattie’s claims were whipping up hysteria not even sixteen months after the sudden and tragic death of Michael Ventris (September 6, 1956). This made it impossible at the time to bring up the following clear fact. Even if Michael Ventris had seen the tripod tablet Ta 641 privately before publishing Work Note 20 and had tested out values, say for the four-sign word-unit now read as ti-ri-po-de, such a test would have been not very different than what Ventris did do with the Knossos tablets (and that Sir Arthur Evans had done in print seventeen years before [Palace of Minos volume 4, p. 799, as reported in Docs², p. 66] in suggesting that the sign sequence *11-*02 could be read using Cypriote values as po-lo = πῶλος) before his use of the ‘Rosetta Stone’ of Linear B, i.e., the Knossos place names and toponymic adjectives.

At some point, within any analyzed code system, lacking a bilingual (or a partially translated encoded message) test values have to be tried by what are hunches as to what particular words might be. ti, ri, po, de, e, me would have done the job in beginning to unlock the grid instead of ko, no, so, pa, i, to. Beattie’s claim that the decipherment announced on the BBC 1 July 1952 had not resulted from analysis of sign occurrences in the texts and positing of test values, but from forcing or manipulating the values deduced from the tripod tablet onto the whole of the then known Linear B texts is in itself absurd. Such a magic trick could not be performed. At the time, however, simply saying “so what?” would have been insufficient. Not that anything ever proved to be sufficient to move Beattie from a position he held at least publicly until he passed from this world into whatever comes next.

Birthday Gift Exhibit D

Birthday Gift Exhibit D is a letter of 19 November 1958 to Bennett. It gives us real insight into the early post-decipherment work on tablets from Mycenae, Knossos and Pylos; into the truly obsessive craziness of Beattie; and into Chadwick’s idea that maintaining contacts through the sending of books and offprints to scholars on the eastern side of the Iron Curtain would be a significant step towards alleviating international political tensions.

We also find in it evidence that the British post-war economy was still Orwellian austere. Chadwick asks Bennett to share the pages he is sending to him with Mabel Lang because “I have neither an extra copy to spare nor can I afford the postage.” On a lighter note, Chadwick comments that he is going to have his wife Joan “put sage on the grocery order” because “I want to repeat your experiment.” Most likely this has to do with Bennett’s publication of The Olive Oil Tablets of Pylos. Texts of Inscriptions Found 1955 (Salamanca 1958) and the sage-scented oil listed in the tablets record.

On page 2, Chadwick speculates as to how information was conveyed between outlying centers and the central palace and refers to “my theory that Pakijana is the community living at Khora (Volimidhia).” He closes by referring to arguments among archaeologists, including Blegen, as to the date of the Knossos tablets. And he ends cryptically:

It was love, by the way.

Any guesses as to the nature of the reference here?

Birthday Gift Exhibit E

Birthday Gift Exhibit E written on New Year’s Day 1959 opens with the salutation “Dear Ahmet” corrected from “Dear Ahmed”—now we know why it was important in Linear B to differentiate voiced from unvoiced dental stops. Chadwick does not wish the joke to go too far and so begins:

(Don’t be alarmed; this is Beattie’s idea of a joke — a parody of commentary of a pseudo-text with all the names twisted; hence you are Ahmet el Pinhed Jr.)

He then goes on to discuss the careful work involved in reaching the third draft of an Appendix with conjectural corrections to existing vocabulary lists, his own new conjectures for readings, and references to published tablet photos in order to aid researchers and teachers who wish to see and use images of the Linear B tablets. A new transcription volume of the Knossos tablets is underway. A “miserable scrap” of a tablet turned up in the “1957 dig at KN.” Chadwick draws the sign as he sees it and asks Bennett whether it is ai or du. Finally Chadwick mentions “my suggested project of photographing all the KN material” and deferentially adds “I hope you won’t think this is cutting you out, or any criticism of your own small scale photos.”

Birthday Gift Exhibit F

Birthday Gift Exhibit F might be called Birthday Gift Exhibit JTK for in this aerogram (dated 23 October 1959) Chadwick reveals to Bennett:

I have a research student (Irish) who wants to work on Lin. B; I can dissuade him, but am wondering if you would think it an insult, if I put him on to duplicate your work on KN hands, at least in part. Not that I don’t trust you, but I think that you would appreciate a second opinion, if reliable. The point is: what actual subject can I give him which will not be superseded by your work within 3 years? I thought of a study of the KN livestock tablets, starting with their epigraphy, hands, scribal procedures and organization; ? location of find-spots, etc. Would you let me know, urgently, what you think of this; or if you can suggest something better, which is not likely to be done elsewhere. If you have a job in mind you would like someone to tackle, here is a chance. It must of course be suitable for a thesis.

This young Irish scholar, of course, is John Tyrell Killen, now emeritus professor of Mycenaean Greek at Cambridge University. This is five years before the appearance of his ground-breaking classic “The Wool Industry of Crete in the Late Bronze Age,” BSA 59 (1964) 1-15. It is also thirty-two and a half years before he visited Luckenbach, TX in April 1992 and discovered that the ‘finishing of lambs’ in the ‘seventeen western states’ of the United States goes back to the practice of o-pa as studied in the Linear B texts (Floreant Studia Mycenaea Band II 1999, p. 332 n. 34). Chadwick then takes up some more bothersome ideas from the scholar he now refers to—hoisting him on his own petard—as B*attie. It seems that B*attie came up with the batty alternative reading in line Bb of the tablet we now know of as Sk 8100 as ko-re-wo instead of the reading of Bennett and Chadwick from actual autopsy as ko-ru GAL. Chadwick’s explanation of how cracks on the tablets may relate to the actual stylus ductus elicited this crackpot response:

“Like Bennett you seem to be a trifle optimistic about cracks in tablets.”

Chadwick continues:

“It is insufferable how he pretends to be able to judge questions of reading, with virtually no experience, and on the basis of a published photograph. He is so rude….”

Birthday Gift Exhibit G

Birthday Gift Exhibit G sent by Chadwick on December 27 1973 announces to Bennett the publication of the second edition of Documents in Mycenaean Greek and fears that a review copy for Nestor sent from the New York office of Cambridge University Press might have gone astray. The cost of the new volume, still never superseded as the ‘bible’ of Linear B studies, $37.50 ($216.54 in 2020 dollars) would have made replacement difficult and the press, writes Chadwick, was being “not at all generous with complimentary copies.”

Chadwick describes in brief his three-month stay in and traveling around Greece during the momentous period from beginning of September to beginning of December 1973 when the country was restless in the seventh year of a repressive rightwing regime. The climate of this time is perhaps best conveyed proleptically by Vassilis Vasilikos’s 1966 novel Z and the Costa-Gavras film (1969) of the same title that won the Oscar for best foreign film.

Chadwick’s wife Joan was with him most of that time. He also reports, with what seems to be an incongruous level of scholarly distraction from the serious realities of everyday life for Greek citizens in a country in its seventh year of a military dictatorship:

“My lectures at the University of Athens were curtailed by student riots followed by a coup—a distinct bore.”

This would seem to refer—with a coda of perhaps ironic rhetorical meiosis—to the courageous student demonstration against the junta of the colonels (1967-74) during the period 14-17 November 1973 that culminated with a tank crushing through the gate of the Πολυτεχνείο sometime after 2 AM on November 17. Unarmed demonstrators were also wounded and killed.

I spoke to a woman in Koroni one summer twenty or so years ago who had been a demonstrator. Her leg was permanently impaired by a bullet that could not be treated at a hospital at the time she was wounded by gunfire for fear that her wounding would be reported and she would be arrested and imprisoned. She had found a politically sympathetic veterinarian to operate on her. This is a clear reminder of how perpetually endangered scholarly freedom is and how easy it is to forget that even humanistic scholarship can divert our attention from greater problems affecting the lives of our fellow human beings.

The letter closes with a query about a young American student:

I wonder what you thought of my former pupil Cynthia Shelmerdine’s article on Ma in AJA, we think here she’s a very bright girl. She is now doing her Ph.D. at Harvard.

She is now Robert M. Armstrong Centennial Professor of Classics emerita at the University of Texas at Austin and the dedicatee of the Festschrift D. Nakassis, J. Gulizio and S.A. James eds., KE-RA-ME-JA: Studies Presented to Cynthia W. Shelmerdine (Philadelphia: INSTAP Academic Press 2014).

Birthday Gift Exhibit H

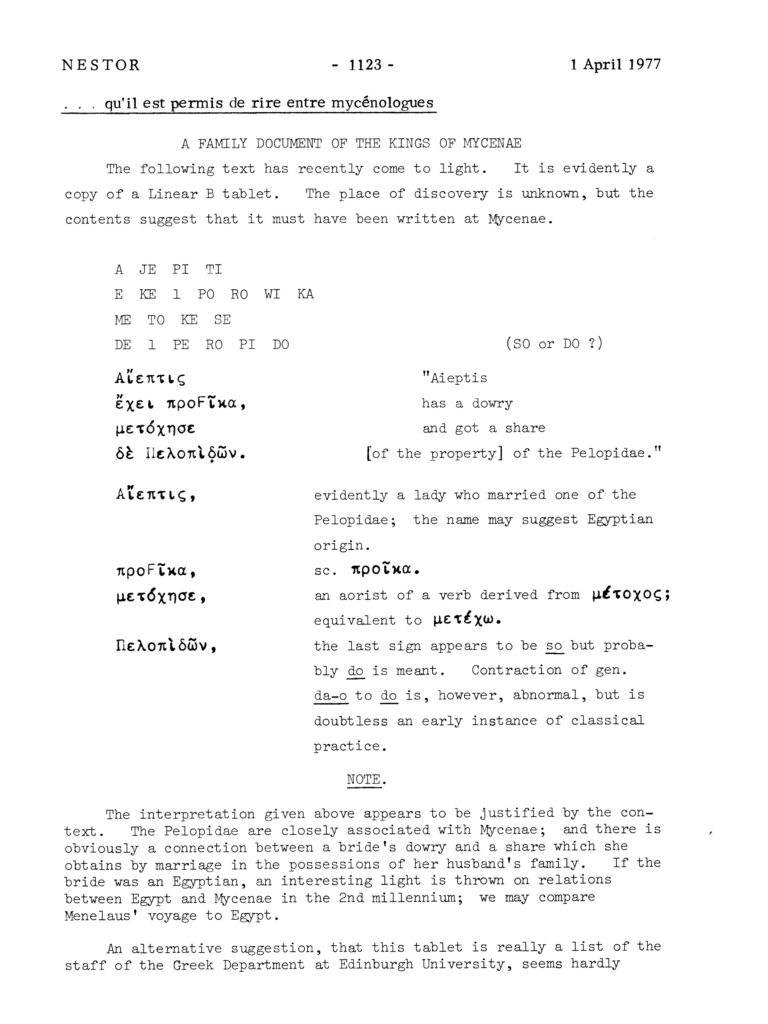

Birthday Gift Exhibit H are the pages of Nestor published on 1 April 1977—note the date—under the rubric . . . qu’il est permis de rire entre mycénologues . Bennett chose this date, well after the fact, to share with interested scholars worldwide a satirical scholarly exchange that took place “[s]everal years ago, before Xerox” and then came back into his memory “[s]ome years later.” In it dueling scholars exchange rival interpretations of a single fabricated Linear B transcribed text that is provided with none of the usual controls upon interpretation associated with Linear B tablets: ideograms and quantities, archaeological find context, associated texts.

References to J. CH*DW*CK, Ch+dw+ck, J.C., Chickweed, J. Chidwock, and Ahmet el Pinhed Jr. in themselves convey the spirit with which these rival interpretations of a contrived document were concocted. The whole is clearly intended to satirize through grossly exaggerated misrepresentation the multivalency of the phonograms in the Linear B syllabary and the supposed ambiguity of the spelling rules. The interpretations make use of great license in proposing alternative readings, correcting purported scribal mistakes, justifying peculiar ways of rendering original sound values and even associating names of faculty members at University of Edinburgh. At the right place at the right time among the right people and under the right circumstances all this could represent good fun.

Bennett was led to think that the time was right in April 1977. I should add that this was ten months before I began my first Linear B seminar from Bennett at University of Wisconsin—Madison. Since I share my mentor’s predilection to encourage laughter among fellow Aegean prehistorians, it is proper to note that I did not meet him until late August 1973, and knew no Linear B even rudimentarily until April 1974. So I had no hand in this publication.

Bennett did deem it a responsible gesture to add the following proviso:

Unfortunately a further word is necessary, since we do not all laugh at the

same things. If you have found the letters funny, and did not notice an incongruity

between the rubric ” . .. qu’ il est perm is de rire … ” and what follows it,

then I did indeed choose the appropriate moment. But if you have been troubled

by it, be assured that this is the only intentional appearance in these pages of

the classic trick for this day: the still-muddy cobblestone under the top hat on

the sidewalk.

We may wonder whether John Chadwick, like Houdini, is spinning around in his grave that these antics are being revived and viewed yet again in the year 2020. We can only add that this is not the only April Fool’s Day tomfoolery in the history of Mycenaean studies. One other example I discussed at length and unfortunately necessarily in all seriousness in the pages of Minos 37-38 (2002-2003) 373-385. But that was long ago and far away.

ἡ γενέθλίος ἡ ἑκατοστὴ εὐτυχής σοι ἔστω.